1970s

Forced Sterilization

Can you imagine a scenario in which a 15-year-old girl goes to the local doctor for routine medical care and returns home having undergone a life-altering sterilization procedure she knew nothing about and didn’t consent to. Imagine if the procedure was carried out by a medical student because he needed more practice. Or the physician wanted to make a little extra income. Or staff were being pressured to prevent poor, minority women from bearing children who might one day be a financial ‘burden’ on the nation. Unconscionable isn’t it?

Yet this scenario isn’t a fiction lifted from some cheap dystopian novel. It’s not the plot of a B-grade television series or twisted philosophy promulgated by fringe politicians. For thousands of women the scenario is all too real. It happened right here in America. In the 1970s. To thousands of American Indian women and girls, and some were as young as 9 years old. Let that sink in for a minute. Yet the majority of Americans have no knowledge of this history. Most wouldn’t believe it anyway, and many couldn’t care less.

“By any objective definition, forced sterilization is a form of genocide“

By any objective definition, forced sterilization is a form of genocide. It has been used by corrupt societies the world over to rid their communities of so-called undesirables – those considered less worthy, more burdensome, and a threat to the dominant caste. The Nazis used it to prevent the birth of more Jews in Germany. It was employed extensively in the Southern U.S. to reduce the African American population. And, like the involuntary taking of Indian children that goes on to this day, forced sterilization was a means to control the American Indian population.

During the 1900s, more than 30,000 non-Indians in 29 U.S. states were sterilized unknowingly or against their will while incarcerated in prisons or housed in mental institutions, and the practice continued in California until 2010. In the five years that followed passage of the federal Family Planning Services and Population Research Act of 1970, some 25-to-50 percent of Native American women of child-bearing age were victims of sterilization without their consent or knowledge.

A U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) investigation looked into four of the 12 regions where the Indian Health Service (IHS) operated, determining that between 1973 and 1976 there were a reported 3,406 procedures that made it into official medical records. Given the shoddy paperwork practices of the day, along with a desire to conceal what was happening, it’s safe to postulate that the actual numbers were much higher. A 1977 report commissioned by the United Nations said the actual figure could be 10 times greater.

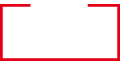

Image: Wikipedia.org

Some of the procedures took place in IHS facilities. Others were carried out in off-reservation hospitals that IHS contracted with to provide services for Native people. At times the women did sign consent forms, but it is unlikely that they understood what was happening or the long-term implications. IHS’ approach to informed consent was wholly mismanaged, and the problem wasn’t unique to sterilization procedures. It’s just how the IHS operated at the time, with constant staff turnover, unmanageable caseloads, and poorly equipped medical facilities. Besides, it was typical for IHS employees to believe that Native people were morally, socially and intellectually inferior and were incapable of managing their own reproductive health. In the end, whether the women consented or not didn’t really matter. The procedures were going to take place regardless.

The two most common procedures were hysterectomies – removal of the uterus through the woman’s abdomen or vagina – and tubal ligations, in which the fallopian tubes are tied, blocked, or cut. Some medical schools at the time did unnecessary hysterectomies on black and brown women as a way for medical students to gain experience. It is believed that a third of these procedures were done on girls under the age of 18 with many under the age of 10.

Ending the ‘Indian problem’

The conduct is clearly reprehensible. The numbers are hard to fathom. But the bigger question that needs to be answered is the ‘why.’ Why did this happen? What was the motivation behind these practices? For the doctors. For the Indian Health Service. For the federal government as a whole. When you consider the totality of U.S. policies and actions taken against the American Indian people over the past 500 years, it’s pretty clear: Forced sterilization was one more way to reduce the number of Indian people, diminish their ability to reproduce, and consequently thwart their political power.

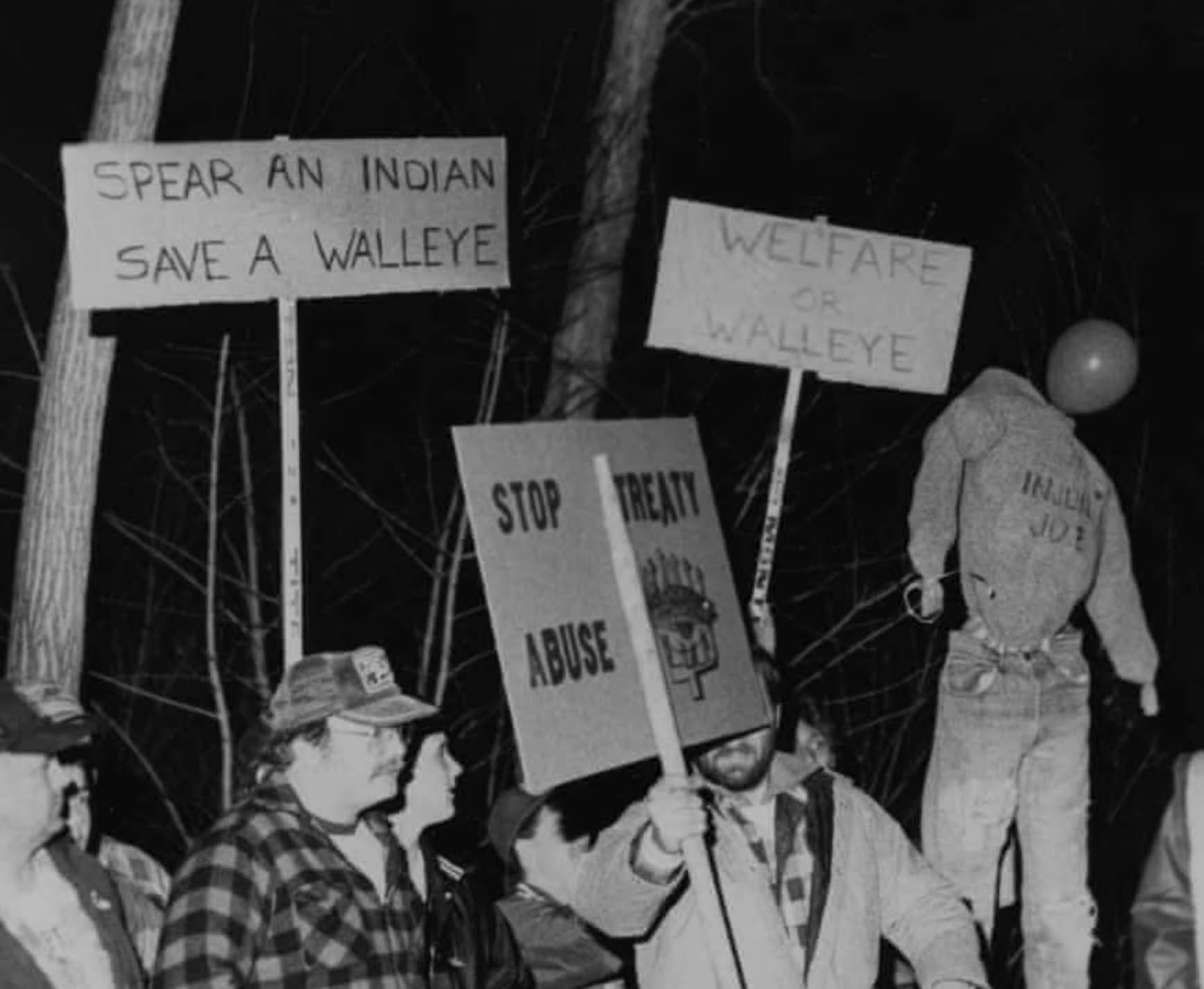

The goal was to eliminate the so-called “Indian problem” long-term. This was also the era that spawned the American Indian Movement (AIM), a ‘radical’ political force that was causing havoc across the country in its efforts to assert ‘Red Power.’ This clearly made white men, along with the government that maintained the social order on their behalf, very uncomfortable. Thus many physicians felt they were doing their patriotic duty by limiting the ability of the ‘radical minorities’ to procreate. Others genuinely believed they were helping the country by reducing the cost of Medicaid, food assistance and social welfare programs.

There were financial incentives for physicians, too. The cost of federal assistance to the poor could eventually lead to increased taxes on higher-income people. There were shorter-term benefits, too, since doctors were often paid for specific procedures carried out. More sterilizations meant a bigger paycheck. Given how poorly paid most IHS personnel were, these were legitimate incentives. Then there was their punishing workload. At the time, there were approximately 1,700 residents for every physician in Indian communities. Fewer babies born meant fewer patients to tend to.

Image: PBS

A trail of destruction

Forced sterilization left a lengthy trail of devastation in Indian communities. The numbers of American Indian babies was already small. Now the birth rate was cut in half. Marriages dissolved because women could not have children. Physical violence against Indian women increased. Rates of mental health conditions, drug and alcohol abuse, and suicide among women of child-bearing age have risen exponentially over time. The matter of missing and murdered Indigenous women is only now entering the consciousness of American people, 50 years after it became an epidemic, and Native women and girls are still being sex-trafficked at an alarming rate.

Today, Indian women have less access to proper reproductive health services than any other women in the country. Since the 1970s, passage of the Hyde Amendment has prohibited federal funding for abortion services with very few exceptions. It is extremely hard for low-income women to get a pregnancy test or terminate a pregnancy, even more so if they live on a reservation and are reliant on a poorly run, vastly underfunded Indian healthcare system. Then, as now, Indian women were easy targets. Relatively small in numbers and largely invisible, it was not difficult for IHS to do the sterilizations without anyone really noticing. It took years of hearings, news reports, investigations, and interviews with victims and those around them to bring these harsh realities to light… for those who actually care to notice.